Scientists are increasingly warning of the potential that a shutdown, or even significant slowdown, of the Atlantic conveyor belt could lead to abrupt climate change, a shift in Earth’s climate that can occur within as short a timeframe as a decade but persist for decades or centuries.

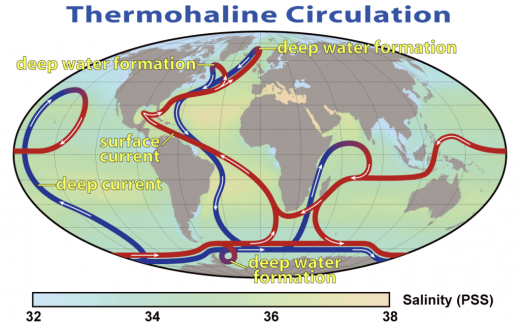

This map shows the pattern of thermohaline circulation also known as “meridional overturning circulation”. This collection of currents is responsible for the large-scale exchange of water masses in the ocean, including providing oxygen to the deep ocean. The entire circulation pattern takes ~2000 years. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Scientists in the Labrador Sea recently made the first retrieval of data from one of 53 lines moored to the sea floor and studded with instruments that have been monitoring the ocean’s circulatory system since 2014.

Held taut by submerged buoys, these moorings are arrayed from Labrador to Greenland and Scotland. In total, five research cruises are planned for this spring and summer to fetch the data the moorings are busy collecting.

The instrument array, known as the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP), measures salinity, temperature, and current velocity of the surrounding water, data that is vital to understanding a set of powerful currents with far-reaching effects on the global climate. These currents are known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) — or, more popularly, “the Atlantic conveyor belt” — and they have “mysteriously” slowed down over the past decade, according to Eric Hand, author of a Science article published this month.

Scientists are increasingly warning of the potential that a shutdown, or even significant slowdown, of the Atlantic conveyor belt could lead to abrupt climate change, a shift in Earth’s climate that can occur within as short a timeframe as a decade but persist for decades or centuries.

North Atlantic waters, such as the Greenland, Irminger, and Labrador Seas, are especially salty when compared with water in other parts of the world’s oceans. When AMOC currents, like the Gulf Stream, bring warmer waters from the south to the North Atlantic, the water cools down, releases its heat to the atmosphere, becomes colder, and sinks, since saltier water is denser than fresher water and cold water is denser than warm water.

In a process called “thermohaline circulation” (“thermos” is the Greek word for heat, while “halos” is the word for salt), this cold, salty water then slowly flows back down into the South Atlantic and eventually makes its way throughout the world’s oceans. At the same time, warm, salty tropical surface waters are drawn northward, where they replace the sinking cold water.

Read more here.