The kings of the Eastern forest now die as shrubs

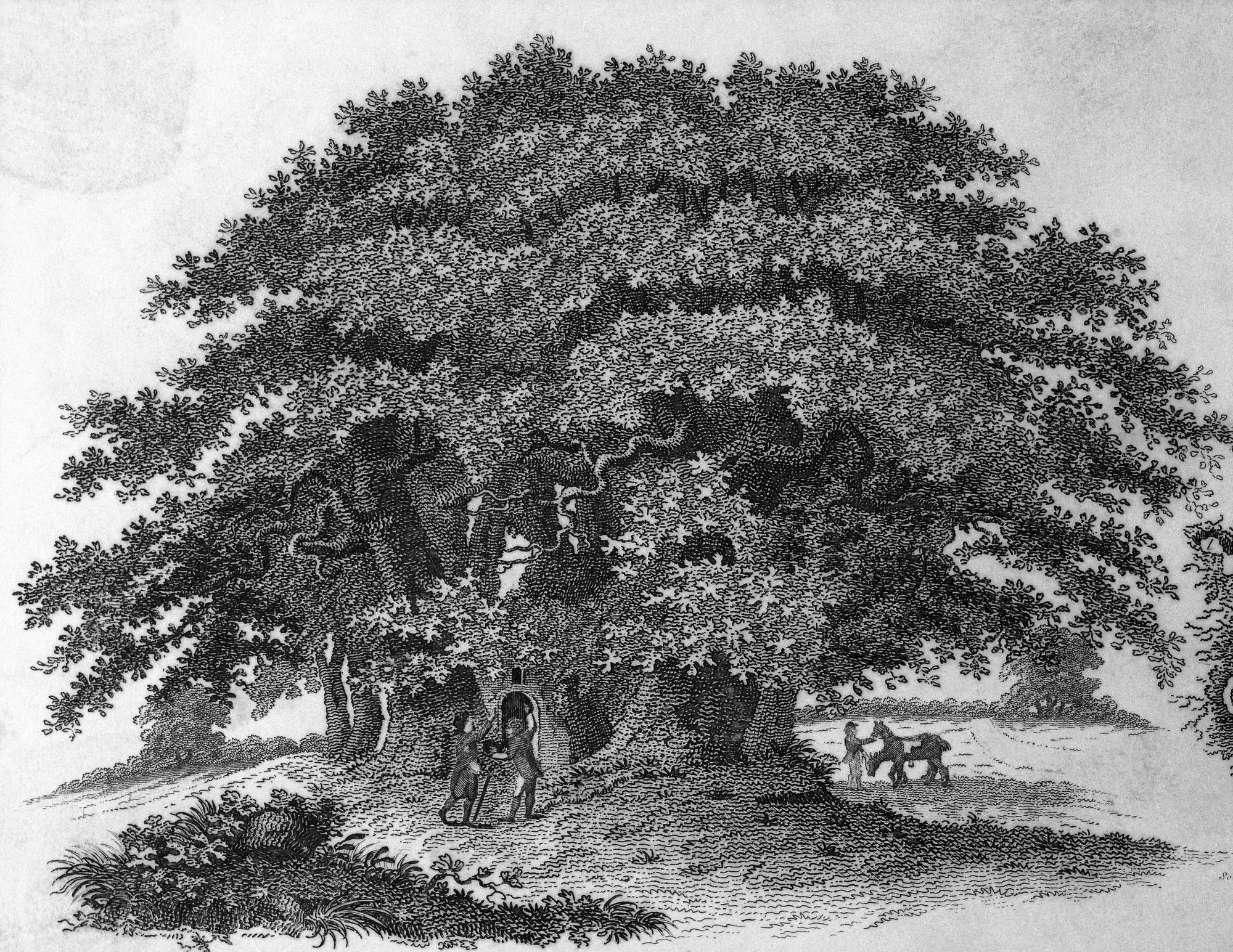

American chestnut trees once blanketed the east coast, with an estimated 4 billion trees spreading in dense canopies from Maine to Mississippi and Florida. These huge and ancient trees, up to 100 feet tall and 9 feet around, were awe-inspiring, the redwoods of the east coast, but with an extra perk — the nuts were edible. Chestnuts were roasted, ground into flour for cakes and bread, and stewed into puddings. The leaves of the trees were boiled down into medicinal treatments by Native Americans. The trees make appearances throughout American literature, like in Thoreau’s journal, where he considered his guilt over pelting them with rocks to shake the nuts loose while he lived in Walden woods, musing that the “old trees are our parents, and our parents’ parents, perchance.” Chestnut trees offered shade in town squares, were the wood of choice for pioneers’ log cabins, and were a mainstay of American woodcraft. In short, chestnuts were part of everyday American life. Until they weren’t.

Finding a mature American chestnut in the wild is so rare today that discoveries are reported in the national press. The trees are “technically extinct,” according to The American Chestnut Foundation. The blight that killed them off still lives in the wild and they rarely grow big enough to flower and seed, typically remaining saplings until they die. Essentially, the giant trees were reduced to shrubs by the 1950s.

The problem was a fungus imported from Asia that spread easily, attaching to animal fur and bird feathers. Spores were released in rainstorms and tracked to other trees through footsteps. The fungus infected trees through injuries to the bark as small as those created by insects. “It looks like a target filled full of small shot holes,” one Pennsylvania paper reported as the blight spread.

The first chestnut tree may have been infected as early as the 1890s, with blight first reported in 1904 when it was spotted on a tree in New York’s Botanical Garden. Panic over the blight was widespread by the 1910s. State commissions were formed. Farmers were implored to chop down trees with any signs of blight. “Woodman, burn that tree; spare not a single bough,” begged The Citizen, a paper from Honesdale, Pennsylvania, the heart of the chestnut tree’s range. Even the Boy Scouts pitched in to try and save the chestnuts, scouring forests for blighted trees as part of a multi-state effort to create an infection-free zone.

The combined powers of the public, scientists, and the governments weren’t enough to save the chestnuts. The loss was stunning, both financially and emotionally. “Efforts to stop the spread of this bark disease have been given up,” The Bismarck Daily Tribune resignedly reported in 1920. The paper estimated that the value of the trees was $400,000,000 as recently as a decade before.

Read more here.