by Michael Smith, RFS, RFA, EcoFor

The management of woodlands and forests by means of coppicing – Niederwaldbewirtschaftung in German – is often, especially elsewhere in Europe, but also in the UK, only seen as a means to produce firewood and, maybe, beanpoles and some charcoal.

However, the products that can be made by means of coppice management of woods and forests is far greater and, in fact, this was the way that we managed our woods and forests in Britain for thousands of years, and that very well and successfully. The woods and forests thrived under this case more and better than under any other form of management.

However, the products that can be made by means of coppice management of woods and forests is far greater and, in fact, this was the way that we managed our woods and forests in Britain for thousands of years, and that very well and successfully. The woods and forests thrived under this case more and better than under any other form of management.

While other countries used this form of woodland and forest management also in the great majority of European countries it has now been abandoned, and has been thus already for many, many decades, in favor of a management that can be done with more mechanized means than coppicing.

The abandonment of coppicing in British woodlands has cost us dearly in terms of almost destroyed woods. In some areas the old coppice stools are almost beyond redemption and this could result in the loss of the entire or almost the entire wood.

The Forestry Commission never did much in that department but then it was not its brief. Its job was the production of timber for the mines and some other applications, including the war effort.

After the Second World War coppicing in our woods started to decline drastically and dramatically, much due to plastic products, and bamboo canes for beanpoles and such rather than wood.

Wooden tent pegs, which were one of the products from coppice woods, were replaced, even by military and scouts with metal and plastic and the same went for so many other products that were once produced from the wood from our coppiced woodlands.

Baskets, once woven from willow from coppicing and pollarding operations, and some other pliable woods, were replaced by plastic and the same for the trugs and such used by bakers and others.

Now, with the revival and renaissance of wood stoves firewood is in great demand but our neglected native woods cannot even provide a small proportion though they could provide it all (at current demand levels) if they would but be managed and we import firewood from as far afield as Poland and Western Russia. Not very sustainable at all.

The same goes for charcoal and most of the charcoal on sale in Britain today, and barbecuing is very much the in thing, also in restaurants, has to come from abroad and, in that case, it comes, primarily, from tropical hardwoods.

The problem, aside from an environmental one, is that that kind of charcoal does not, unlike the local one, light easily and requires chemical accelerants in the form of barbecue fire lighters. Those, however, leave a residue and not just on the coal.

Before the “advent”, so to speak, of coal, charcoal fired the Industrial Revolution in Britain and while it, probably, caused some deforestation, most of it was sourced from coppice operations.

Wooden spoons, spatulas and other wooden kitchen utensils were once made by local craftsmen from local coppiced timber but from a certain time onwards those were made from often imported woods by factories and now the great majority of those utensils are made, in fact, abroad, in the main, nowadays, in China.

In times past almost everything wood came from local woodlands, with the exception of some furniture, that were under coppice management and the woods and the craftsmen prospered.

Coppicing is one of the best ways to maintain the health of woodlands and this system of management has great benefits for the environment. In addition to this this old way of woodland management also will benefit the local economies and that is too very important indeed.

Our woodlands and forest must be brought back under this age old management system in order to restore them to health and for the local economy of craftsmen and -women to be revitalized.

Unfortunately misguided environmentalists for years have been working against this as they, having read only those books that back up their own beliefs, believe that no tree should ever be cut down, for any reason.

In fact many have vehemently campaigned and forced, for lack of a better word, local authorities, woodland and forest owners and managers to leave woods in their “natural” state or allow them too “return” to a wildwood state. But there is no wildwood in the British Isles and has not been any for at least a millennium or more. Not that that has interested those.

Woodlands, many of them state with venom in their voices, do not need to be managed. Nature will do it all itself. Which is a false notion as, alas, left to their own devices those, formerly managed woods, will decay and that will the end of them.

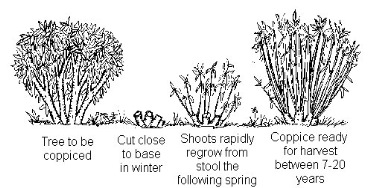

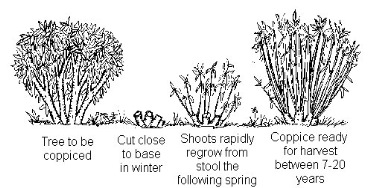

Coppice stools that are not cut will, in the end, break apart and that often almost simultaneously and thus the woods are no more but just a piece of useless “wilderness”.

As soon as brambles and bracken take over – and this is very soon if a wood is not managed – and then not controlled the loss of habitat follows in a very short space of time. Brambles and bracken stop light getting to the woodland floor, and the same is true when the woodland is not being thinned, and anything of value will die and be smothered. But, they keep claiming, Nature will manage it all itself; it just takes a while.

This is not true, however, and man has to keep the regime of management that our forefathers began many hundreds of years ago if we wish to retain those woods and forests.

For thousands of years we have managed our woodlands and forests, more often that not by coppicing, and they thrived under our care and if we want them to thrive again we must bring those woods and forests that have been neglected back under this management regime and it must be done now, before it is too late.

© 2013

The last three years has seen the emergence of a new generation of woodland co-ops. Back in January in the steep hills of Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire, our co-op, Blackbark Woodland Management, hosted the first 'Coppice Co-ops Conference' which brought together Blackbark, Leeds Coppice Co-op, The Coppice Co-op in Cumbria and Rypplewood Coppice Co-op from Bristol. It was a charmed weekend, with a magical collision of ideas, advice, problem sharing, honesty and friendship. There were full daytime programmes of serious discussions, followed by delicious laugher and serious fun into the early hours.

The last three years has seen the emergence of a new generation of woodland co-ops. Back in January in the steep hills of Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire, our co-op, Blackbark Woodland Management, hosted the first 'Coppice Co-ops Conference' which brought together Blackbark, Leeds Coppice Co-op, The Coppice Co-op in Cumbria and Rypplewood Coppice Co-op from Bristol. It was a charmed weekend, with a magical collision of ideas, advice, problem sharing, honesty and friendship. There were full daytime programmes of serious discussions, followed by delicious laugher and serious fun into the early hours.