by Michael Smith (Veshengro)

“...everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor, or they will never be industrious.” ~ Arthur Young,1771

Our popular economic wisdom – and what the people are told – says that capitalism equals freedom and free societies. But is the really the case? The short answer to this is a firm no. It is slavery in all but name.

Instead of the master the owner of a business is referred to in capitalism as the employer, or worse still in the German language as “giver of work”, while the slave is called “employee” or, let's quote a German translation again “taker of work” which the “giver of work” out of his kind heart (please take not: sarcasm) makes available to the worker. You still with me here?

While in the old days of slavery the slave owner had to look – more or less – after his investment, the workers, house them, clothe them, feed them, in wage slavery the owner pays the slave who then has to use the little money for such things as food, clothing and housing. Often the housing was provided by the factory even which means that the owner got money back for more often than not hovels, and many also had to buy their provisions in factory stores. But they were free. Yeah, right!

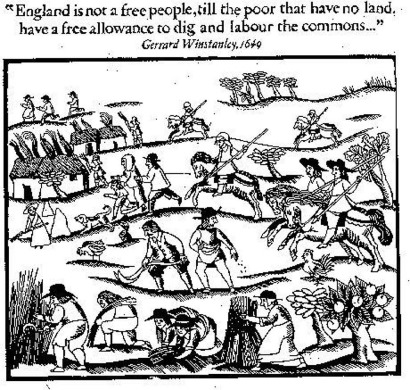

This transition to a capitalistic society did not happen naturally or smoothly. The English peasants did not want to give up their rural communal lifestyle, leave their land and go work for below-subsistence wages in dirty, dangerous factories being set up by a new, rich class of landowning capitalists. And for good reason, too.

The peasant – the independent peasant – in his community was self-reliant if not even more or less self-sufficient. He did not need much in the way of coin, of money, to get the thing he and his family needed. While the factory slave had to toil for days to afford to buy a pair of commercially produced shoes or boots the rural peasant could make his own of an evening, often clogs with a leather upper, for instance, or had them made paying in kind.

But in order for capitalism to work, capitalists needed a pool of cheap, surplus labor. So what to do? Call in the National Guard? Well, in a manner of speaking yes.

Faced with a peasantry that did not feel inclined to playing the role of slave, philosophers, economists, politicians, moralists and leading business figures began advocating for government action. Over time, they enacted a series of laws and measures designed to push peasants out of the old and into the new by destroying their traditional means of self-support.

The serious brutal acts associated with the process of stripping the majority of the people of the means of producing for themselves are very much at odd with and very far removed from the reputation of people having had free choice in this matter as often portrayed by proponents of classical political economy.

Many different policies were enacted through which peasants were forced off the land – from the enactment of so-called Game Laws that prohibited peasants from hunting, to the destruction of the peasant productivity by fencing the commons into smaller lots – and even that did not immediately bring the peasants flocking to the towns and cities and into the factories.

The proto-capitalist were openly complaining and whining about how peasants are too independent and comfortable to be properly exploited, and were trying to figure out how to force them to accept a life of wage slavery.

Pamphleteers of that time got busy in decrying the laziness of the peasants and their indolence and those paragraphs below will show the general attitude of those capitalists and their supporters towards successful, self-sufficient peasant farmers:

“The possession of a cow or two, with a hog, and a few geese, naturally exalts the peasant. . . . In sauntering after his cattle, he acquires a habit of indolence. Quarter, half, and occasionally whole days, are imperceptibly lost. Day labour becomes disgusting; the aversion increases by indulgence. And at length the sale of a half-fed calf, or hog, furnishes the means of adding intemperance to idleness.”

While another pamphleteer wrote:

“Nor can I conceive a greater curse upon a body of people, than to be thrown upon a spot of land, where the productions for subsistence and food were, in great measure, spontaneous, and the climate required or admitted little care for raiment or covering.”

John Bellers, a Quaker “philanthropist” and economic thinker saw independent peasants as a hindrance to his plan of forcing poor people into prison-factories, where they would live, work and produce a profit of 45% for aristocratic owners:

“Our Forests and great Commons (make the Poor that are upon them too much like the Indians) being a hindrance to Industry, and are Nurseries of Idleness and Insolence.”

Daniel Defoe, the novelist and trader, noted that in the Scottish Highlands “people were extremely well furnished with provisions – venison exceedingly plentiful, and at all seasons, young or old, which they kill with their guns whenever they find it.”

To Thomas Pennant, a botanist, this self-sufficiency was ruining a perfectly good peasant population:

“The manners of the native Highlanders may be expressed in these words: indolent to a high degree, unless roused to war, or any animating amusement.”

Having a full belly and productive land was in their eyes the problem, and the solution to whipping those “lazy bums” into shape was obvious: kick them off the land and let em starve. And that is exactly what was done...

Arthur Young, a popular writer and economic thinker respected by John Stuart Mill, wrote in 1771: “everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor, or they will never be industrious.” Sir William Temple, a politician and Jonathan Swift's boss, agreed, and suggested that food be taxed as much as possible to prevent the working class from a life of “sloth and debauchery.”

Temple also advocated putting four-year-old kids to work in the factories, writing “for by these means, we hope that the rising generation will be so habituated to constant employment that it would at length prove agreeable and entertaining to them.” Some thought that four was already too old. According to Perelmen, “John Locke, often seen as a philosopher of liberty, called for the commencement of work at the ripe age of three.” Child labor also excited Defoe, who was joyed at the prospect that “children after four or five years of age... could every one earn their own bread.”

To combat any dissent of the peasants conscripted by force to be wage slave the Reverend Joseph Townsend believed that restricting food was the way to go: “[Direct] legal constraint [to labor] . . . is attended with too much trouble, violence, and noise, . . . whereas hunger is not only a peaceable, silent, unremitted pressure, but as the most natural motive to industry, it calls forth the most powerful exertions. . . . Hunger will tame the fiercest animals, it will teach decency and civility, obedience and subjugation to the most brutish, the most obstinate, and the most perverse.”

Patrick Colquhoun, a merchant who set up England's first private “preventative police” force to prevent dock workers from supplementing their meager wages with stolen goods, provided what may be the most lucid explanation of how hunger and poverty correlate to productivity and wealth creation: “Poverty is that state and condition in society where the individual has no surplus labor in store, or, in other words, no property or means of subsistence but what is derived from the constant exercise of industry in the various occupations of life. Poverty is therefore a most necessary and indispensable ingredient in society, without which nations and communities could not exist in a state of civilization. It is the lot of man. It is the source of wealth, since without poverty, there could be no labor; there could be no riches, no refinement, no comfort, and no benefit to those who may be possessed of wealth.”

So, just to let that think in a little more here I repeat the important part from the above: “Poverty is therefore a most necessary and indispensable ingredient in society... It is the source of wealth, since without poverty, there could be no labor; there could be no riches, no refinement, no comfort, and no benefit to those who may be possessed of wealth.”

So much for the historic part, and more, so to speak.

Hunger, as advocated by the good Reverend Joseph Townsend, is still today used as a weapon against the working class and for the fear of becoming destitute and homeless the worker will even accept cuts in wages and conditions so as to keep his job (and home). The threat of loss of employment – for the worker does not have a cottage and garden to fall back on and some cottage industry skills that can make him a little money on the side, like the peasant has/had – and thus loss of home and more will keep the worker in line, so to speak, and a good ample supply of unemployed is also necessary for this.

The Irish Famine also has to be seen in this context and the same light for it had less to do with the potato harvest failing due to the blight but everything to do with the fact that the powers-that-be wanted to rid the countryside of the independent peasant.

Full employment is bad for capitalism and the capitalist and thus there has to be a pool of unemployed maintained under conditions worse than under the worst employment so that there remains always the threat from the master to the slave that the slave might be joining that pool if he or she does not do as ordered. That is how the capitalist masters maintain their hold over the workforce and nowadays even the trade unions, more often than not, help to keep the worker in chains rather than helping him to throw off those shackles, as in the case, for instance, most recently in Germany where the IG Metal, the metal workers' union, has colluded with the employers that temporary workers can be used by a company for several times greater a time span, before they have to become permanent employees, as the government has decreed.

Not only did the independent (minded) peasants had to be forced off the land and into the cities and the factories to create wage slaves for the capitalists, even the independent craftsmen had to be destroyed, as both were in the way for capitalism to develop.

It is for that very reason that the powers-that-be are making it as difficult as at all possible for anyone wishing to take up smallholding, for instance, or living and working in a wood, even if they own that land or wood. The independent peasants and woodsmen, as well as craftsmen, are a threat to them still to this very day as they do not fit in with the plans of capitalism.

© 2017